Four Questions with Jonathan Louis Duckworth

I had the pleasure of meeting author Jonathan Louis Duckworth at StokerCon 2023 in Pittsburgh. I’m delighted that he took the time to stop by Tamika Talks Terror ahead of the summer release of his debut speculative story collection from JournalStone Publishing. His answers to my four questions are thought-provoking, and I might never look at stars the same again.

Tamika Thompson: What is horror?

Jonathan Louis Duckworth: I think this requires disambiguation because we could be talking about either a genre or an effect. I’m not very interested in investigating and taxonomizing genres (I leave that to more organized brains like Michael T. Cisco or Tzvetan Todorov) so I’ll speak about the effect.

Stephen King argues that you can delineate the effects of horror fiction into three levels, revulsion (lowest), horror (mid-level), and terror (high-level), and I think that’s a useful way of thinking about what we do when we attempt to write “horror.” For King, horror as the middle tier effect of aberrant writing is the presentation of the “unbelievable,” those things which our minds are ill-suited to comprehending and digesting. Okay, so what do I think, personally?

In my doctoral dissertation, I briefly defined horror as “a repellant effect, any stimulus that creates in the reader a strong sense of aversion from said stimulus in the aftermath of its reception.” I contrast horror with other effects like the sublime, which, in my reckoning, produces awe or wonder at a force already spent (e.g. marveling at Ozymandias’s ruins), or terror, which extracts dread from the occasion of some force, event, or entity’s imminent approach. But more casually, I think horror is an inoculation. We enjoy these things that unnerve or unsettle us because, in the same way we’d inject ourselves with a dead virus to withstand its living counterpart, we want to metabolize our fears in the controlled environment of fiction.

Almost every horror writer I know, myself included, far from being fearless, were easily frightened as children and possibly still jump at every sound in the dark. The horror writer’s imagination is almost invariably overactive and attuned to catastrophizing. If disaster fiction asks the question “what if everything that could go wrong did go wrong?” then horror fiction poses a refinement: “what if that plus a lot of impossible things went as wrong as possible?” Horror is the perception of that wrongness as it occurs, and also the thrill that—after all—this is all just a book/movie/video game and we were never in danger.

Thompson: What is the spookiest experience you've ever had?

Duckworth: This is going to be a bit of a copout. For all that I delight in researching and imagining the supernatural, I’m a stone-cold materialist. I don’t believe in an afterlife or in ghosts or in any cryptid that hasn’t already been revealed and catalogued by scientists. With that said, I’m also a giant wimp with an overactive (and overly reactive) imagination. This may sound silly, but my spookiest experiences have always been when I look up at the night sky and see the stars. Some people are soothed by stars, but not me—stars scare the hell out of me.

There’s something inarticulable about their horror, their vastness and how incalculably old they are compared to us, but that also paradoxically they could already be dead and we wouldn’t know it for another hundred years when the belated light finally stops reaching us. There is an abstract, mathematical horror to looking at a twinkling star, realizing it could fit everything you’ve ever known inside of its gaseous body a thousand times over, or worse yet that that little point of light isn’t a star at all but a galaxy made up of trillions of stars, or even a galaxy cluster. I don’t know if this makes sense to anyone but me, but I personally can’t look at the stars without shivering.

Thompson: What is the scariest book you've read and what about it frightened you?

Duckworth: No horror novel I’ve ever read has been as brutal or disturbing as Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. It’s not technically horror (or at least not marketed as such) but you’ll never convince me it isn’t a stealthy cosmic horror novel masquerading as a literary Western. With Judge Holden, McCarthy (Rest in Peace) created possibly the most evil figure in all literature, an uncanny and mysterious entity who seems as inevitable as he is impossible. The violence is stomach-turning but somehow never gratuitous because the novel’s gnostic cosmology makes every brutal execution or senseless act of savagery feel natural within the narrative’s amoral logic.

If you asked me about actual horror books, I’d probably say The Wingspan of Severed Hands by Joe Koch. Stories about madness are a weakness of mine, and Joe’s surreal logic and corrosively elegant prose captures so well the mind-dissolving terror of Carcosa and The Yellow Sign from Robert Chambers’ mythos.

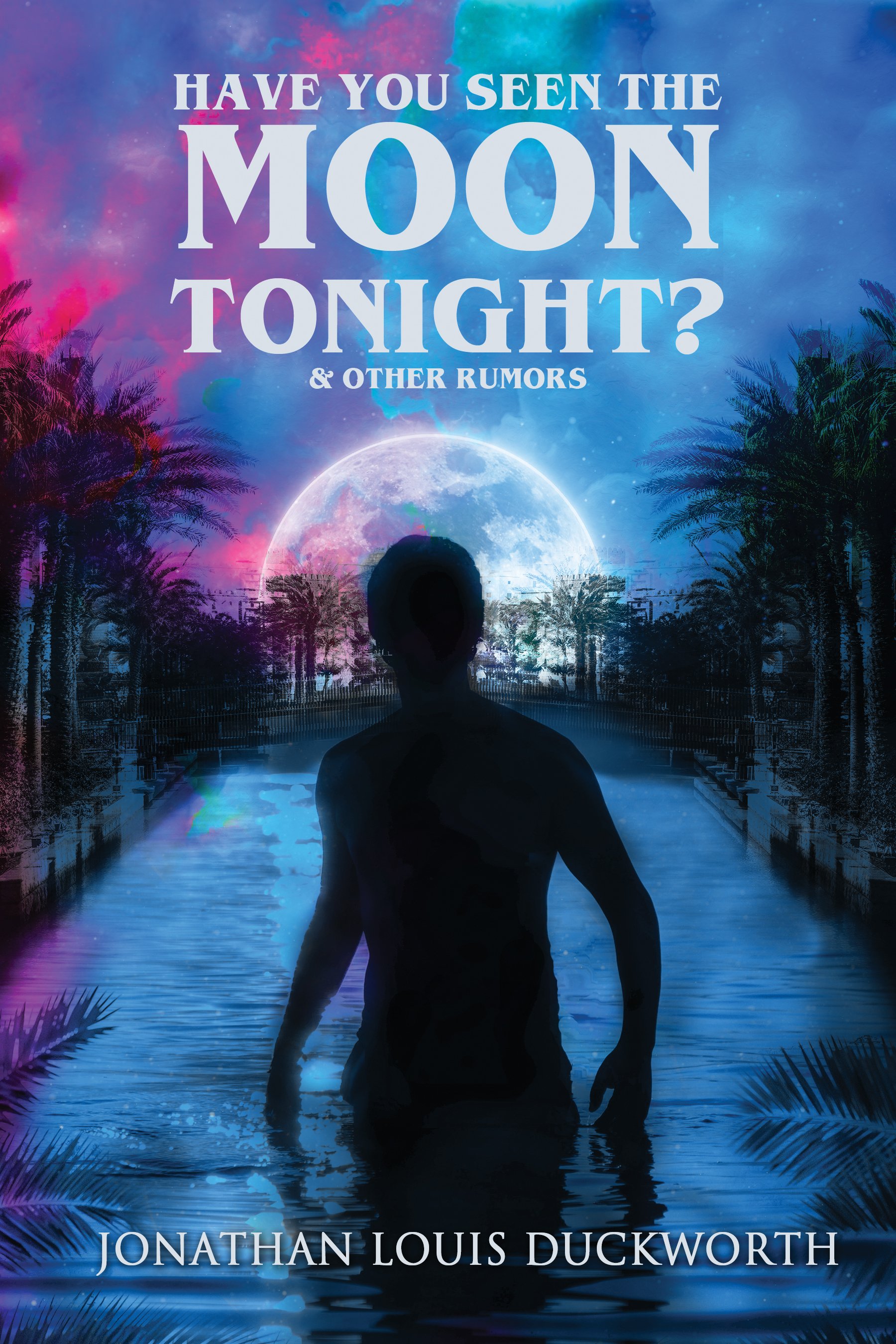

Thompson: In your upcoming debut story collection, Have You Seen the Moon Tonight? & Other Rumors, many of the stories, like the one in which language becomes a plague, include events that end the world. What was the inspiration for creating these scenarios?

Duckworth: I often struggle to remember the inspiration for individual stories months or even years after first writing them. I think that’s a good thing, though. In poetry, there’s the concept of the poem transcending its poetic subject, and similarly, I think when a story succeeds it transcends and outgrows the germ from which it was inspired. That said, a lot of these scenarios are born from two places: just looking at what the world’s becoming, or my overactive imagination.

A few of the stories take an ecocritical posture, considering how these scenarios either arise from our very real climate catastrophe or as a punishment for our inaction. Other scenarios are more inspired by vague misgivings, such as the title story, which concerns a strange shadow on the moon which drives people insane and turns them into “moonheads.” In this case, for as much as the stars terrify me, the moon has always been a calming presence, a symbol of serenity, and for the moon to become something sinister and dangerous would be the ultimate horror for me.

Other stories explore my fear of disconnection, like “Paper Wings in the House of Light,” where the protagonist has been so divorced from human society that he’s lost touch with his humanity and has to rediscover it in the eponymous house of light, or “The Rumor” where language (my first and truest love) betrays humanity in the form of a word-plague that robs people of their sanity and bodily autonomy. Through all the stories there’s often ambivalence about whether the end of the world would be the horror, or if the true horror is the status quo that the world’s end is disrupting.

One thing worth remembering is that the concept of the “end of the world” is full of unstated assumptions about what the world is and what it would mean for it to “end.” For some people, the end of the world could mean the collapse of our social order, but if that social order itself is evil and unfair, is that the worst thing that could happen? I tend to write stories from the perspectives of those outside the political establishment, those whose lives are not comfortable, whose needs are not being met. These are the people who are most vulnerable to catastrophes and most likely to be hurt when sea levels rise or mass violence breaks out, but they also have less to lose from the destruction of the status quo than those with all the power and comfort, and potentially more to gain if the world as it is collapses and becomes something else. I think it’s this ambivalence and this potentiality that I try to capture with a lot of my stories—this horror could destroy you, but it could also set you free.

Jonathan Louis Duckworth is a completely normal, entirely human person with the right number of heads and everything, and he loves folktales and playing with language. He received his MFA from Florida International University. His speculative fiction work appears in Fantasy & Science Fiction, Pseudopod, Southwest Review, Tales to Terrify, Flash Fiction Online, and elsewhere. He is a PhD student at University of North Texas, an active HWA member, and the current interviews editor at American Literary Review.